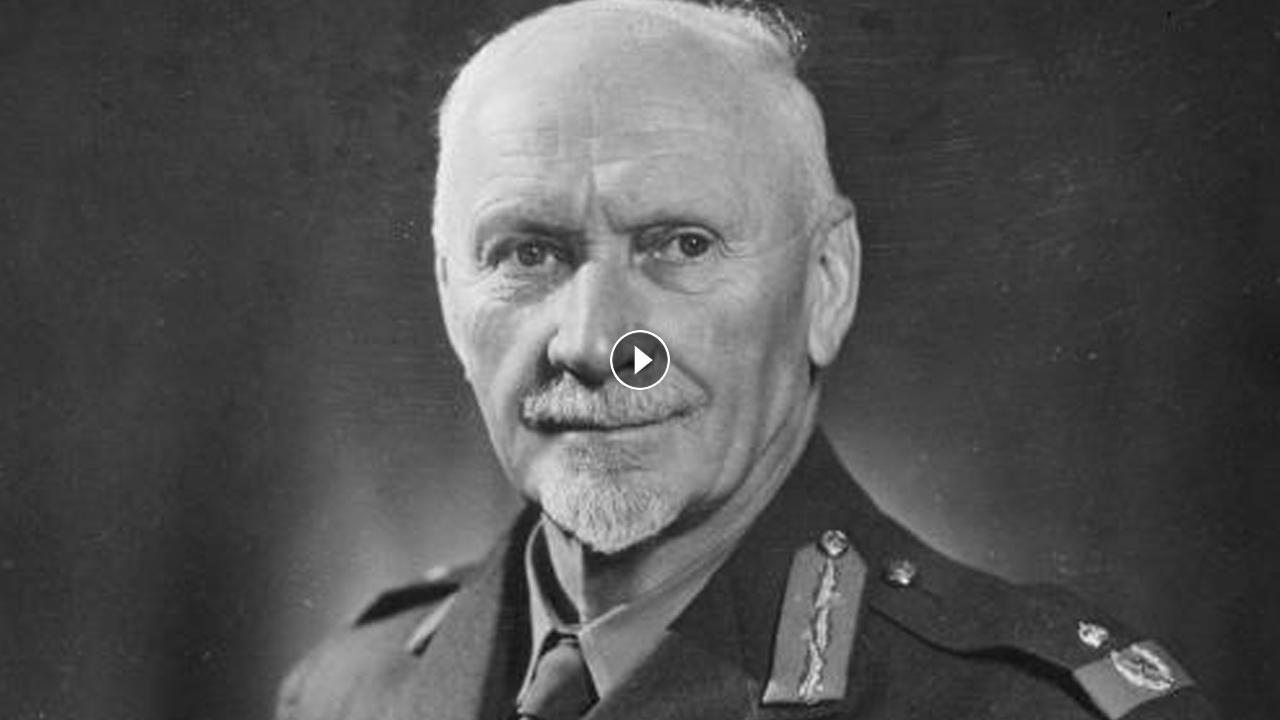

Jan Smuts, in full Jan Christian Smuts, Christian also spelled Christiaan, (born May 24, 1870, Bovenplaats, near Riebeeck West, Cape Colony [now in South Africa]—died Sept. 11, 1950, Irene, near Pretoria, S.Af.), South African statesman, soldier, and prime minister (1919–24, 1939–48), who sought to promote South Africa as a responsible member of the (British) Commonwealth.

Early Life And Career

Jan Christian Smuts was born on a farm near Riebeeck West in the Cape Colony. His ancestors were mainly Dutch, with a small admixture of French and German but no English, though he was born a British subject. Until he went to school at the age of 12, Smuts lived the life of a South African farm boy, taking his share in the work of the farm, learning from nature, and developing a life-long love of the land. Many years later, when asked by an American botanist why he, a general, should be an authority on grasses, Smuts replied, “But my dear lady, I am only a general in my spare time.”

At 16 he went to Victoria College (subsequently the University of Stellenbosch), where he studied science and arts and obtained first-class honours in both. At Stellenbosch he fell in love with a fellow student, Isie Krige, whom he later married and who remained a source of strength through the stresses and strains of an eventful life.

In 1891 he obtained a scholarship and entered Christ’s College, Cambridge, where he read law and was generally recognized as one of the most brilliant law students Cambridge had had. He was the first ever to take both parts of the law tripos examinations in the same year, and in both he came first. From Cambridge he went to London, where he came first in the Inns of Court honours examination and was awarded two prizes. It seemed clear that a distinguished academic career lay ahead of him; nevertheless, Smuts wanted to return to South Africa.

Apart from law he read widely in philosophy, poetry, and science, and it was at this time that he first read the poems of Walt Whitman. Many years later he compared the effect that Whitman had on him to St. Paul’s experience on the road to Damascus. Whitman’s conception of natural man liberated him, he believed, from the sense of sin induced by a strict Calvinist upbringing. Before he left England he wrote a book about Whitman but failed to find a publisher.

Returning to Cape Town in 1895, Smuts was at once drawn into politics. At first he supported Cecil Rhodes, prime minister of Cape Colony. But the raid of L.S. Jameson on the Transvaal destroyed his confidence in Rhodes, and, finding himself without political attachment and with insufficient legal work, Smuts decided to move to Johannesburg. At the end of 1897 he married Isie Krige, moving to Pretoria a year later when he was appointed state attorney by Pres. Paul Kruger. At the age of 28 he was thus at the centre of Transvaal politics and, in effect, at the centre of South African politics. From then until his death he was continuously involved in South African and world affairs.

Role In The Boer War

For the first nine months of the South African (Boer) War, which began in October 1899, Smuts was part official and part soldier, moving between Pretoria and the front. When Pretoria was occupied by the British he became a full-time soldier, eventually receiving an independent command. He was an apt pupil in the guerrilla tactics that were so successfully exploited against the overstretched British lines of communication. In April 1902 he invaded the Cape Colony—to within 120 miles (190 kilometres) of Cape Town, but by then his force was too little and too late. When the war ended he had to be recalled, under British escort, to take part in drafting peace terms.

The Boers lost their independent republics, but Smuts remained firm in his belief in the future of a united South Africa. He returned to Pretoria and family life but was inevitably drawn into public affairs. He and Gen. Louis Botha combined to oppose the high commissioner Alfred Milner’s narrow interpretation of the peace terms and to insist on Boer rights. It was a remarkable partnership, in which Smuts supplied the intellectual vigour and Botha a deep knowledge of his fellow men and great wisdom in dealing with them. Their first objective was responsible government for the two former republics; after that would come union of the four colonies. Smuts played a major role in the achievement of responsible government for the Transvaal (1906) and the Union of South Africa (1910).

When Smuts went to England at the end of 1905 to urge the Cabinet to give the Transvaal self-government he came to know a new English world. At Cambridge he had known few Englishmen, and after his return to South Africa he had to devote his energies to fighting the British. But from 1905 his personal friends in England were the intelligent, liberal-minded people whom he now began to meet. To them he escaped from the exacting and exhaustingly boring official social life of London; with them he found the intellectual and spiritual refreshment that, because of long absences, he too seldom enjoyed at home. He had the reputation of being cold and aloof, but among his friends and in his own family circle he was a different man—relaxed and genial, fond of and easy with children.

Role In World War I

Just as Smuts was drawn into the public life of his own country, so, after the outbreak of World War I, he was drawn into international affairs. When he and Botha had suppressed rebellion in South Africa, conquered South West Africa, and launched a campaign in East Africa, he went to England for an imperial conference (March 1917). Prime Minister Lloyd George at once recognized his abilities and made him minister of air. From then on he was used in a variety of tasks. He organized the Royal Air Force and was concerned in all major decisions about the war. At the peace conference at Versailles, the English economist J.M. Keynes regarded him as the greatest protagonist of a moderate peace that would not crush Germany, and he may justly be called one of the principal progenitors of the League of Nations.

A few months after their return from Versailles, Botha died, and Smuts became prime minister. Nearly five years later he was defeated by a coalition of the Nationalist and Labour parties and remained in opposition until 1933, when he and J.B.M. Hertzog joined forces against the more extreme nationalists. Smuts was content to serve under Hertzog, but they were in deep disagreement about whether South Africa should go to war if Britain did. When the crisis came in September 1939 Smuts’s view prevailed by a narrow majority of 13 in Parliament. Smuts became prime minister, and South Africa declared war on Germany.

During World War II South Africa played a much greater part than in World War I, but Smuts himself was not as important a figure as he had been during 1914–18. He was consulted by Sir Winston Churchill and other Allied leaders, but his main role was to prevent Germany and Italy from conquering North Africa. Once that objective was achieved, he and his country became of relatively minor importance. Smuts represented South Africa at the 1945 San Francisco Conference at which the Charter of the United Nations was drafted.

At the general election of 1948 Smuts’s party was defeated by the Nationalists. D.F. Malan became prime minister, and one of his first acts was to offer Smuts an official airplane to go to Cambridge, where he was to be installed as chancellor, an offer that Smuts accepted. Two years later, at his home near Pretoria, he died.

Legacy

Despite his great abilities and achievements, Smuts was not a popular leader—he had a subtle and sophisticated mind, was impatient, could not tolerate mediocrity, was immensely hardworking, and had no time for the sociabilities that make for popularity. For almost half his lifetime—from 1912 to 1950—he was derided, mistrusted, reviled, and even hated by an increasing majority of his fellow Afrikaners. He was called a lackey of the empire and a betrayer of his own people. Before and during the South African War he was staunchly anti-British and in favour of a united Afrikaner people.

In 1917 and 1919 he persuaded British statesmen to grant dominion status and (in 1920) to drop the word empire. It was believed by some that Smuts was trying to break up the empire. In fact, he knew that the only way to preserve it was to allow as much independence as possible to its components. Nationalist Afrikaners knew this, too—hence, their detestation of Smuts. He was a great South African; they wanted him to be a great Afrikaner. He wanted an independent South Africa closely linked with the Commonwealth; they wanted an independent republic outside the Commonwealth. Ten years after his death the Nationalists achieved their aim.

- Category

- Biographies